Classical Concert Music

Alluvial Gold (2020)

For Percussion Soloist and Electronics

The work was commissioned by Louise Devenish and Erin Coates and funded through a Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries grant. The work has been performed at the Perth Festival (2021), Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA) Hatched Season (2022), the Four Winds Music Festival (2023), and the Melbourne Recital Centre (2023).

The work was commissioned by Louise Devenish and Erin Coates and funded through a Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries grant. The work has been performed at the Perth Festival (2021), Perth Institute of Contemporary Art (PICA) Hatched Season (2022), the Four Winds Music Festival (2023), and the Melbourne Recital Centre (2023).

The work Alluvial Gold is a solo work for a mix of percussion, sculptures as instruments, installation, and electronics. The work explores the confluence of multiple narratives about the Swan River, from the phenomenological and structural aspects of river systems and water, the storytelling and histories before European colonisation, the devastating impact of industrialisation, the sonic ecology and chemistry of the larger river system, and a musical language derived from transcriptions of water and the sculptures used. In the work, the river forms a temporal narrative through a changing sound world and aesthetic, an expression of the composers' own sense of belonging to place, and the Sacred identity of Derbarl Yerrigan. The basis of this work is thanks to a longer term collaborative project with Melbourne-based percussionist Louise Devenish and Perth-based visual artist Erin Coates.

The work is comprised of nine movements, and whilst these movements were conceived to be presented as one continuous performance without a break totalling approximately 45 minutes, each movement was written in such a way that they could alternatively be presented individually.

The nine movements are as follows:

The work is comprised of nine movements, and whilst these movements were conceived to be presented as one continuous performance without a break totalling approximately 45 minutes, each movement was written in such a way that they could alternatively be presented individually.

The nine movements are as follows:

- Material - Source - Object (7'00")

- Confluence (4'30")

- The Cascades (approx. 3'00")

- Alluvial Fans and Meanders (4'30")

- Spiritual Water in the Mouth of the River (approx. 5'30")

- Crystalline Water in the Mouth of the River (approx. 4'00")

- Death in the Mouth of the River (8'44")

- The Place of the Eagle (approx. 4'00")

- Engulfment - Emancipation (approx. 3'30")

En'Coda (2020)

For 2 vocalists, shruti box, crystal bowls, didgeridoo, string orchestra, and percussion. The work was commissioned by Tenille Bentley, and based on songwriting by Tenille Bentley and January Kultura.

eliquescence | agglutination (2017)

For marimba, prepared piano, bass, 3 snare drums and a large ensemble of open instrumentation.

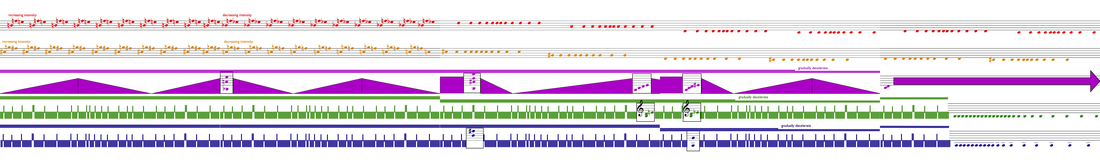

The premise for this work is largely concerned with a theoretical framework was proposed by Albert Bregman, auditory scene analysis (ASA). One of the theories this framework proposes is one of auditory 'stream fusion' and 'stream segregation.' This work explores stream fusion and segregation through a metric and rhythmic impetus. The metaphorical processes explored here are of the scientific concepts of liquefaction versus solidification. The changes in atomic bonds that occur when materials change state are expressed musically through the 'quantised' nature of the rhythmic relationships allocated to the ensemble. The score uses hybrid notation, combining common practice notation with graphic notation. The Decibel ScorePlayer is used as a conductor. A click track is also distributed only to certain conductor/performers. The work explores poly-tempo and free materials coexisting with material with a precise rhythmic intent. There is an underlying melodic and rhythmic motif that is transformed and manipulated throughout.

The premise for this work is largely concerned with a theoretical framework was proposed by Albert Bregman, auditory scene analysis (ASA). One of the theories this framework proposes is one of auditory 'stream fusion' and 'stream segregation.' This work explores stream fusion and segregation through a metric and rhythmic impetus. The metaphorical processes explored here are of the scientific concepts of liquefaction versus solidification. The changes in atomic bonds that occur when materials change state are expressed musically through the 'quantised' nature of the rhythmic relationships allocated to the ensemble. The score uses hybrid notation, combining common practice notation with graphic notation. The Decibel ScorePlayer is used as a conductor. A click track is also distributed only to certain conductor/performers. The work explores poly-tempo and free materials coexisting with material with a precise rhythmic intent. There is an underlying melodic and rhythmic motif that is transformed and manipulated throughout.

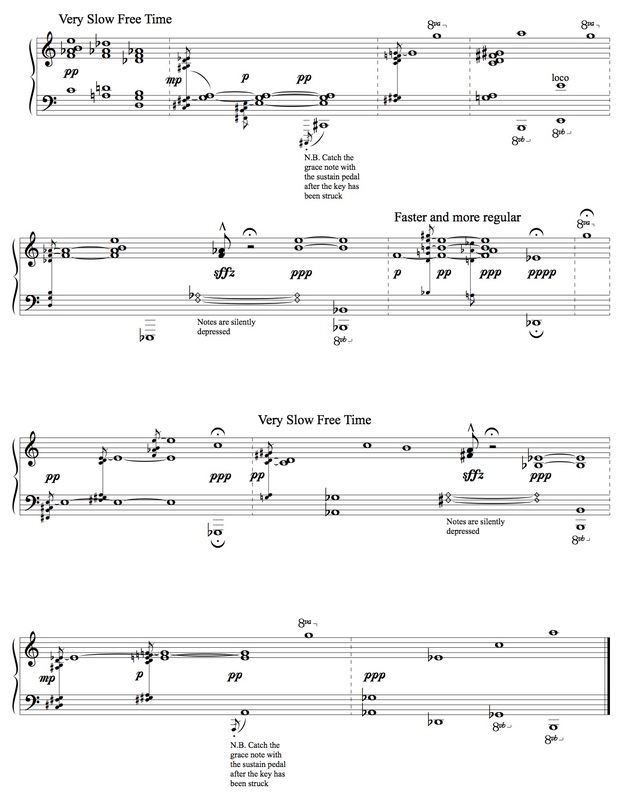

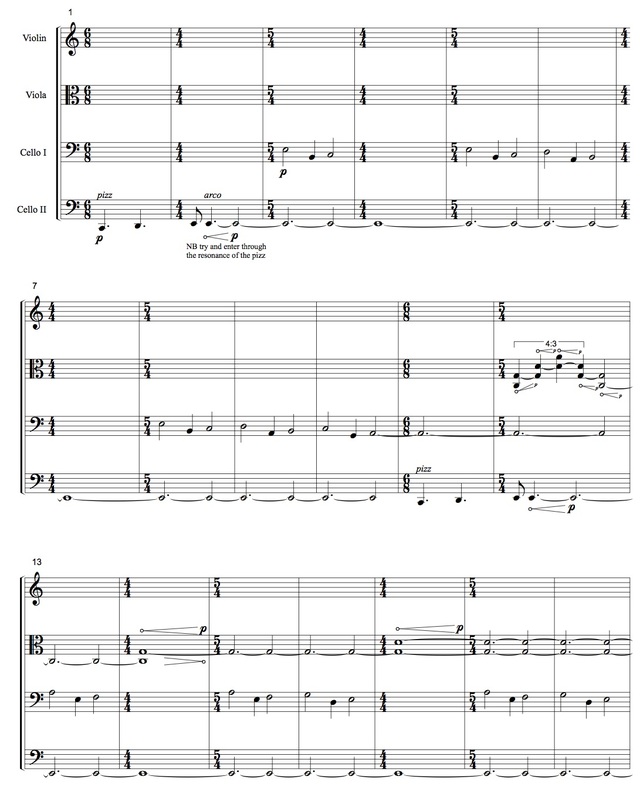

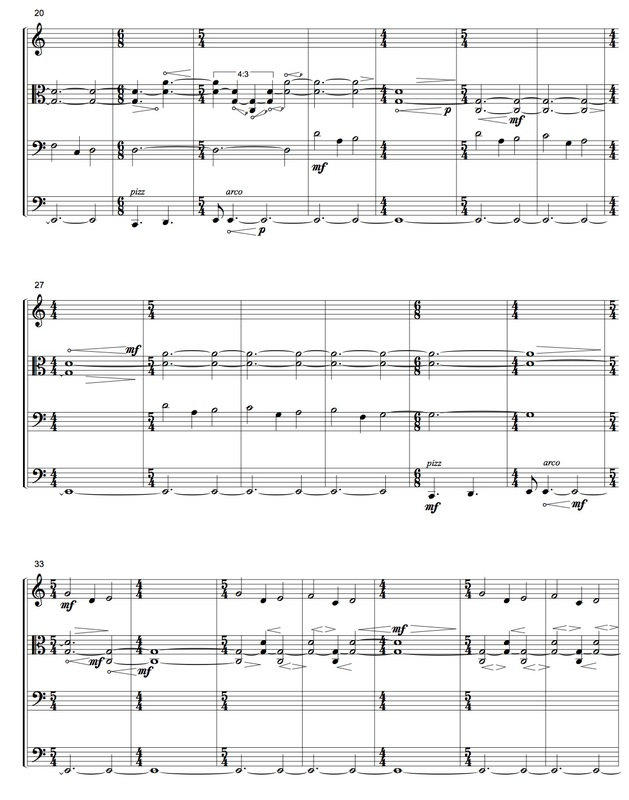

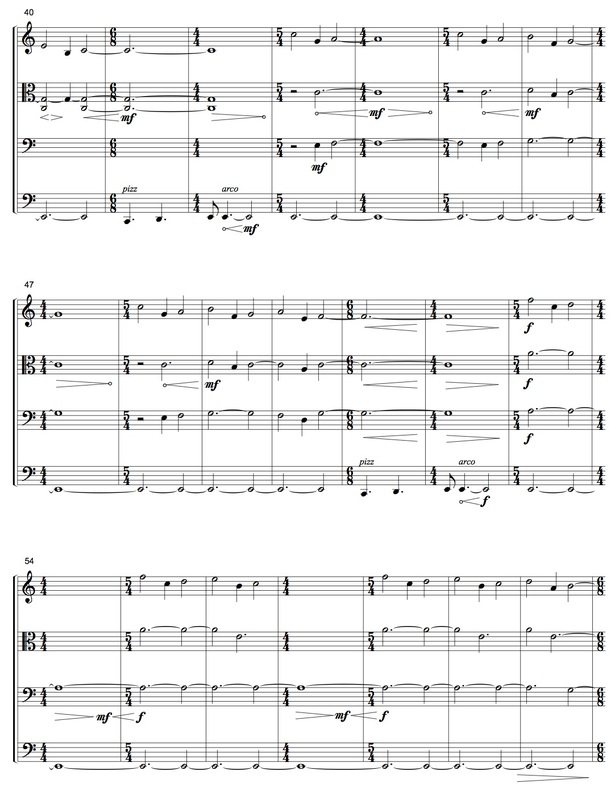

A Song for My Beloved (2017)

For Piano Quintet. The premiere performance featured the Sartory String Quartet with the composer on piano

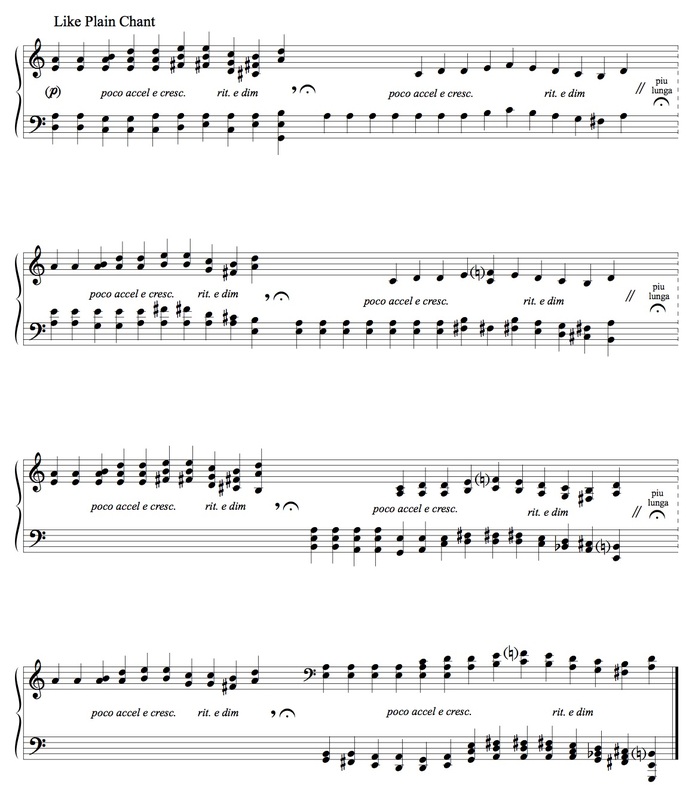

The work is a dedication to the composers’ fiancee Marjorie Angco, who has been living oversees. They have both been in a long distance relationship for almost 3 years, awaiting approval of a Visa so she can move to Australia and marry. This is the first strictly acoustic chamber work by the composer , as he has been largely writing exclusively electroacoustic and electronic works in recent years. The work explores influences found in the works of Josquin De Prez, Monteverdi, J.S. Bach, Fauré, Satie, Milhaud, Poulenc, Tippett, Barber, Górecki, Pärt and songwriters Björk and Nick Cave.

The work is a dedication to the composers’ fiancee Marjorie Angco, who has been living oversees. They have both been in a long distance relationship for almost 3 years, awaiting approval of a Visa so she can move to Australia and marry. This is the first strictly acoustic chamber work by the composer , as he has been largely writing exclusively electroacoustic and electronic works in recent years. The work explores influences found in the works of Josquin De Prez, Monteverdi, J.S. Bach, Fauré, Satie, Milhaud, Poulenc, Tippett, Barber, Górecki, Pärt and songwriters Björk and Nick Cave.

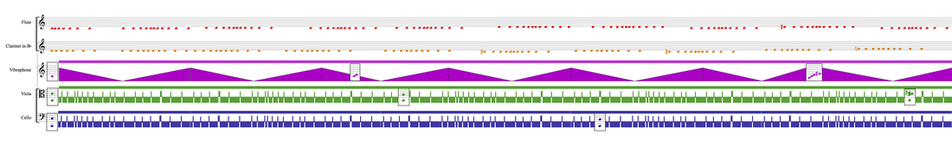

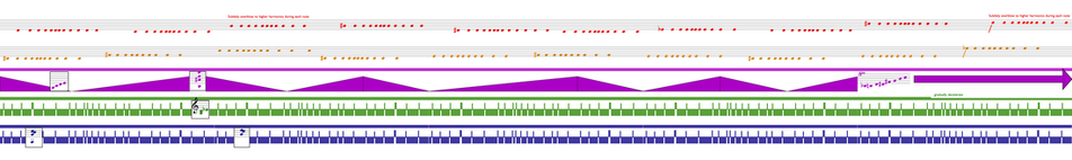

Remembrance (2016)

Commissioned by Decibel New Music Ensemble

Piano, Flute, Clarinet, Vibraphone, and Live Electronics (stereo)

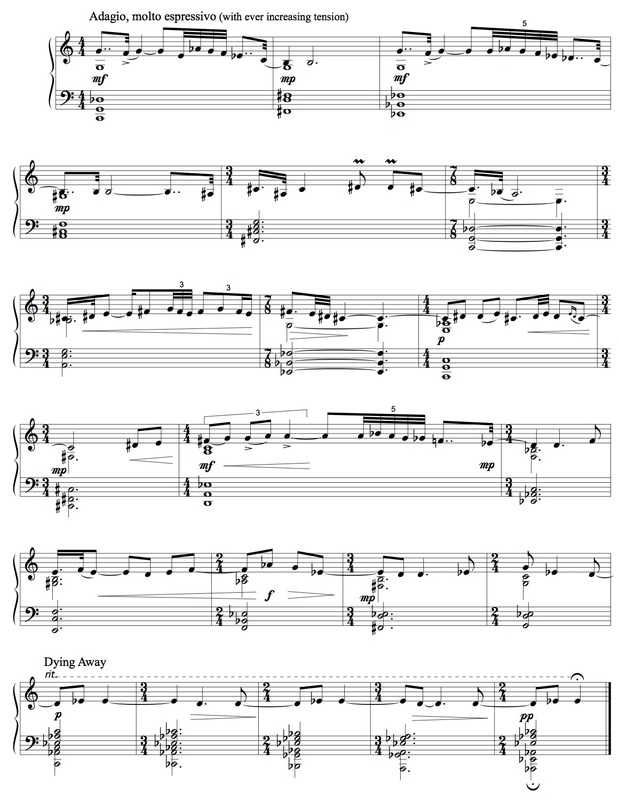

The work explores elements that are recalled through visual memory versus material that is learned through muscle memory and repetition. The score asks players to recall passages that explore the same geophysical shapes from memory before recalling passages performed previously within the work from memory prompted with written cues. Some sections of the work explore new materials, whilst distracting other performers from remembering sections they had performed previously.

Piano, Flute, Clarinet, Vibraphone, and Live Electronics (stereo)

The work explores elements that are recalled through visual memory versus material that is learned through muscle memory and repetition. The score asks players to recall passages that explore the same geophysical shapes from memory before recalling passages performed previously within the work from memory prompted with written cues. Some sections of the work explore new materials, whilst distracting other performers from remembering sections they had performed previously.

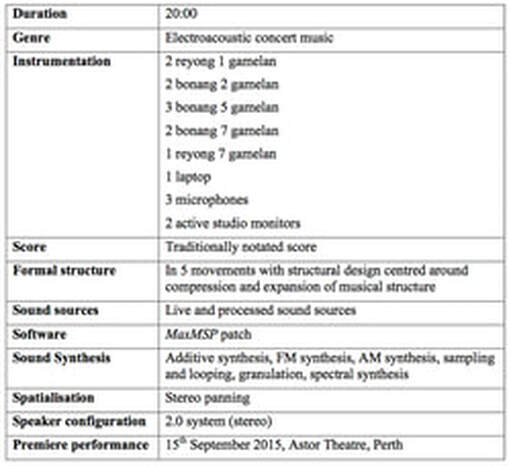

Kinabuhi | Kamatayon (2015)

Commissioned by Louise Devenish

For Reyong and Bonang Gamelan and Electronics (stereo)

For Reyong and Bonang Gamelan and Electronics (stereo)

|

|

"Now these semi-abstract gestures are suddenly traded for a 4/4 emphasis and a tonal centre (it seems to be a minor key), see-sawing chimes forming a suspenseful ostinato that won’t let up. At this moment I discern traces of techno, of ambient electronica and Steve Reich, whether or not these evocations are intended or welcomed. ...Ultimately the piece consists of countless minimalist melodies rendered with a range of inflections, overlapping, repeating, jostling. The piece is said to reflect upon the sun, the moon, the tides, nature, breathing, life, death… but before I’ve been told this, I get some unarticulated sense of it. There’s something reverent and deep and pensive happening." Lyndon Blue (Cool Perth Nights, 2015)

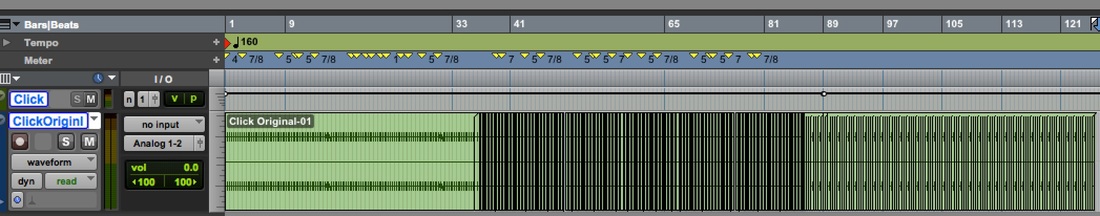

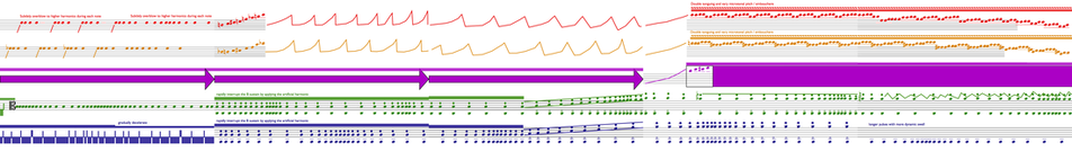

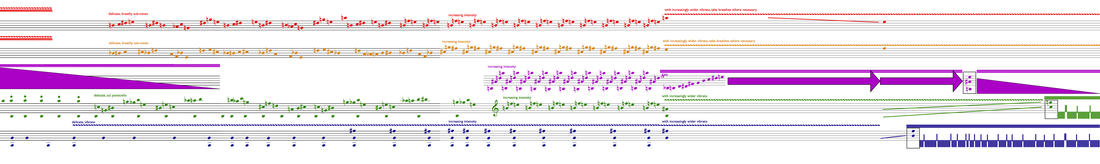

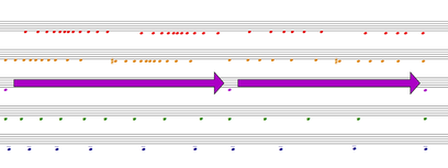

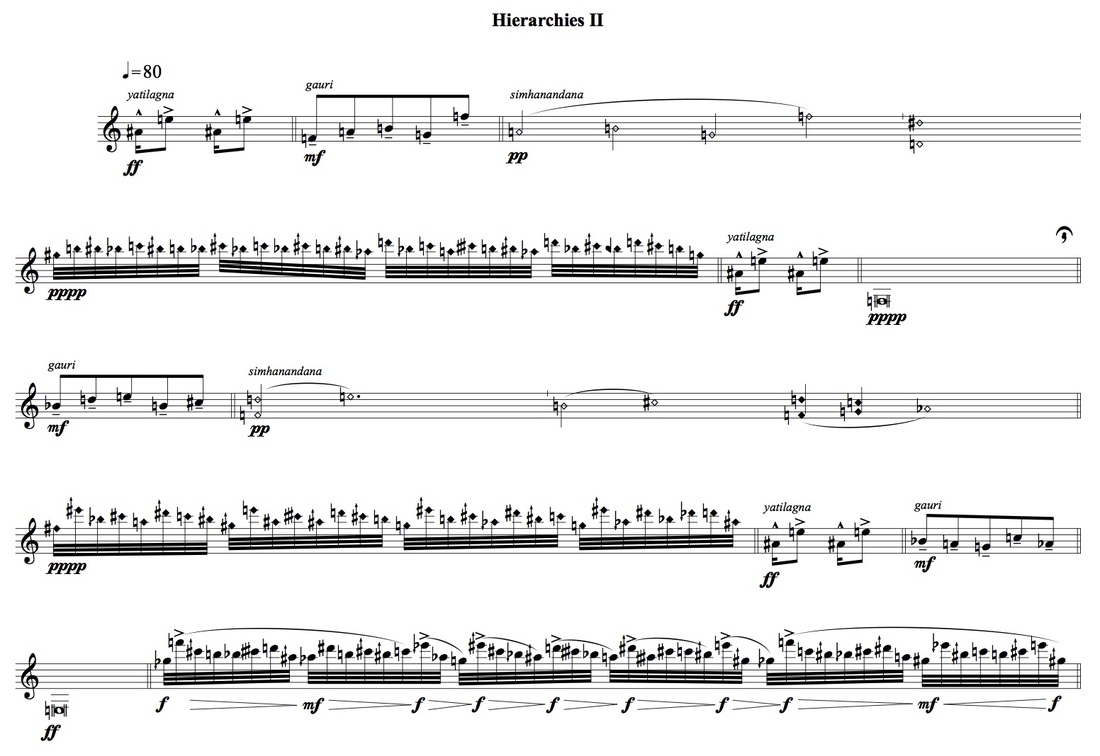

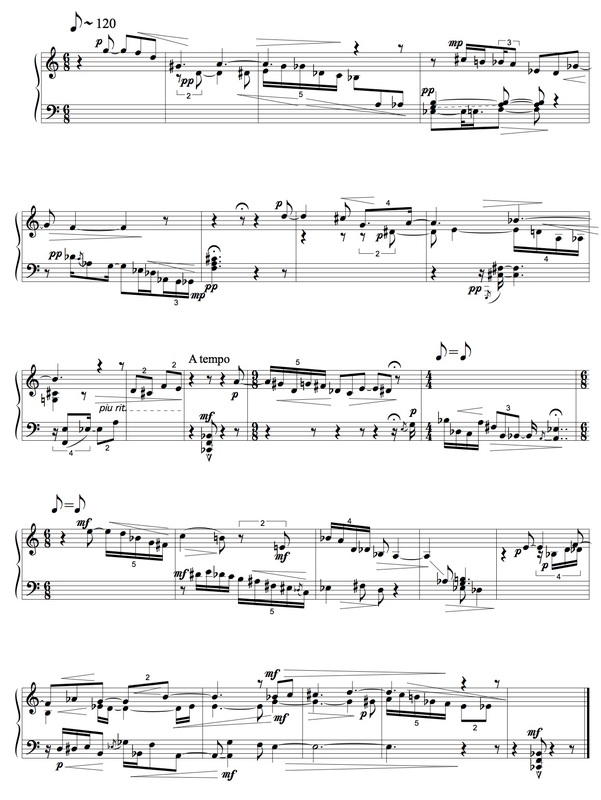

The essence of energy consists of the cycles of life and death. The sun, the moon, the tides, the planets, the seasons, the oscillation of wings. The essence of human life is the breath, the compression and rarefaction of the lungs. The essence of sound is the compression and rarefaction of kinetic energy passing through air. The work Kinabuhi | Kamatayon is both a celebration of life and death, and is itself concerned with the compression and rarefaction of time. The work is divided into five movements, and progressively transitions from a compression and rarefaction across an entire movement to transitions between consecutive bars in movements 1 and 5 respectively. The work explores different time scales, sometimes in parallel or in series. Ensuring the tempo ratio's are synchronised to the sample for Movement 4 of 'Kinabuhi | Kamatayon' for Reyong and Bonang Gamelan, and Electronics (commission from percussionist Louise Devenish). The nested tempo ratio's are supposed to reveal a fractal-like structure of different tempo specific materials by iterating the same metric modulation (tempo ratio). All rhythmic groups are odd causing consistently overlapping rhythms. |

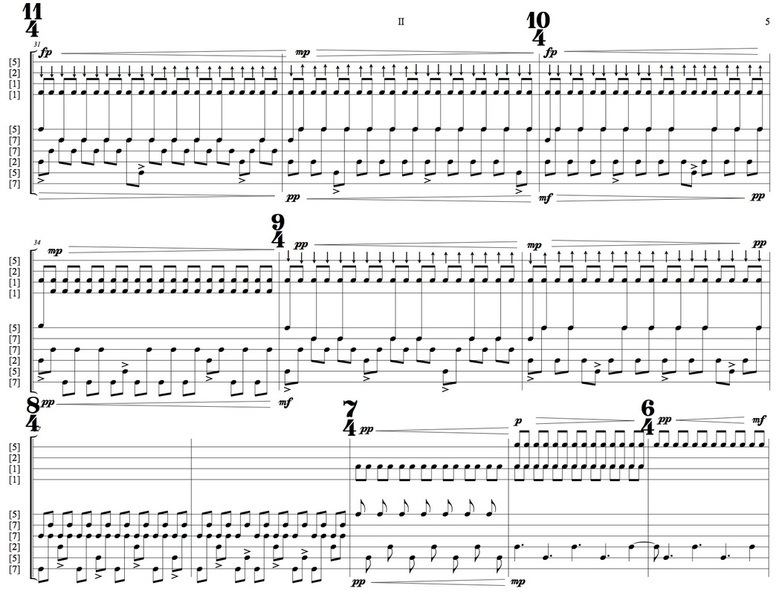

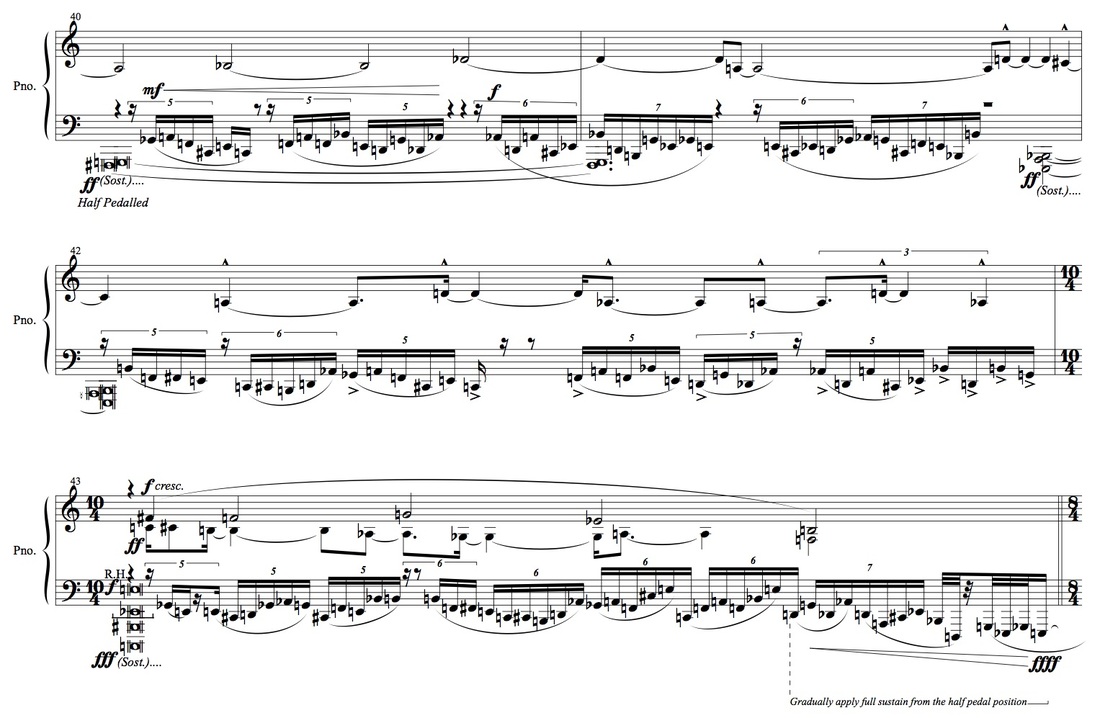

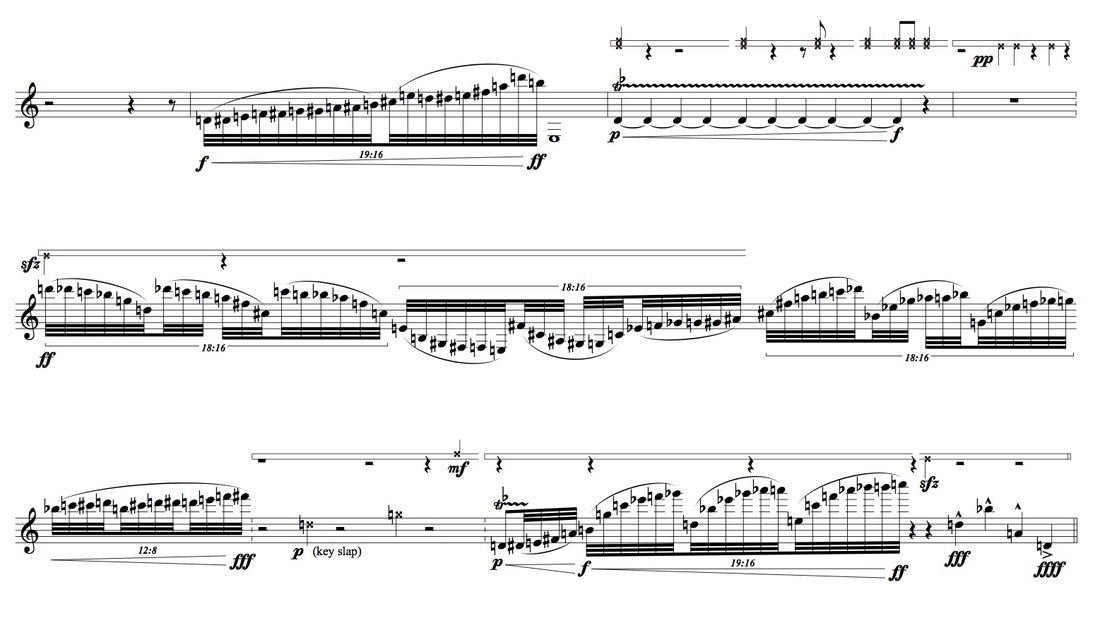

Timbre shaping and multiple tempo canons in Movement 2 of 'Kinabuhi | Kamatayon' for Reyong and Bonang Gamelan, and Electronics (commission from percussionist Louise Devenish)

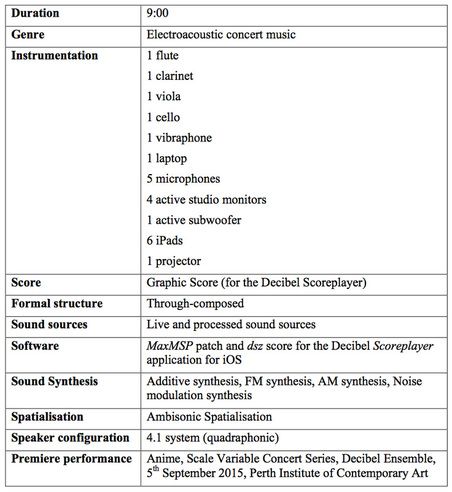

Existence Éphémère (2015)

For Flute, Clarinet, Viola, Cello, Vibraphone and Electronics (4.1 surround sound)

Commissioned by Decibel New Music Ensemble

Commissioned by Decibel New Music Ensemble

|

"We can, if we so choose, wander aimlessly over the continent of the arbitrary. Rootless as some winged seed blown about on a serendipitous spring breeze. Nonetheless, we can in the same breath deny that there is any such thing as coincidence. What's done is done, what's yet to be is clearly yet to be. In other words, sandwiched as we are between the "everything" that is behind us and the "zero" beyond us, ours is an ephemeral existence in which there is neither coincidence nor possibility." ― Haruki Murakami, A Wild Sheep Chase

An exploration of the psychoacoustic phenomenon known as stream fusion. The piece plays with the threshold of ones ability to discern separate streams as individual layers, or a fusion of layers that interact in a complex way. The piece explores unfolding note groups outlining a harmonic language derived around major 7ths. This is also explored in the sound synthesis resulting in accumulated timbres of stacked major 7ths. |

n-dimension (2013)

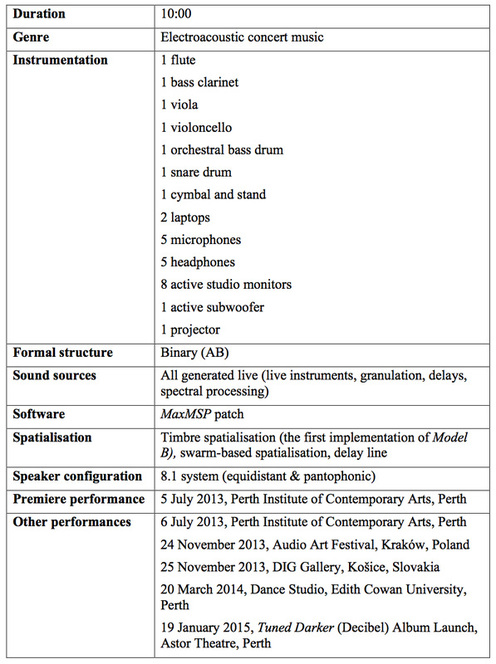

For Flute, Bass Clarinet, Viola, Cello, Percussion and Live Electronics (8.1 surround sound)

The scientific study of objects and spaces is often described in terms of an n-dimensional topological or topographical space, where n is a number representing the dimensionality. Standard Euclidean spaces and objects have whole number dimensions, and fractal dimensions are described as having

fractional dimensions. This composition began as an exploration in musical structures, from fractal and infinite pitch series, fractal rhythmic structure, tempo canon, chaotic controlled spatialisation and audio feedback. The work ‘elaborates’ on the dimensionality of a small collection of simple musical structures in order to arrive at a more complex and immersive listening experience.

N-Dimension was a commission for the Decibel new music ensemble while I was involved in a week-long artist residency in the Perth Institute for Contemporary Arts. It is a work written for flute, bass clarinet, viola, cello, percussion and electronics. This is a chamber ensemble work that utilises multiple acoustic instruments processed in real time. Although it was performed and workshopped with eight speakers, it could be easily adapted for other speaker configurations. Other performances of this work were presented at the Audio Art Festival in Kraków, Poland, and the DIG Gallery in Košice, Slovakia, in 2013 and at ensemble Decibel’s Tuned Darker album launch at the Astor Theatre, Perth in 2015.

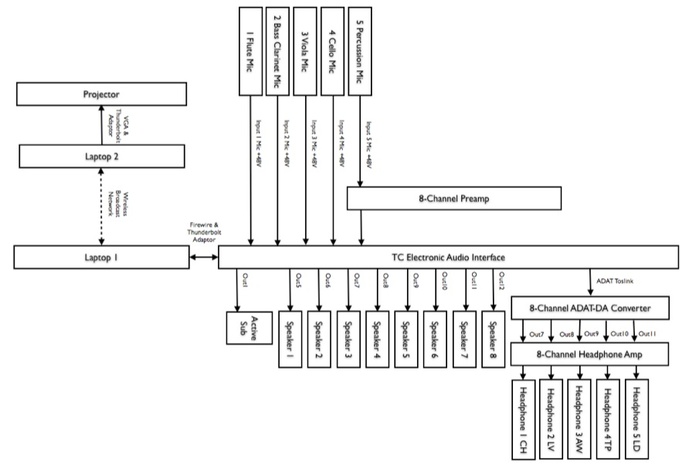

The technical setup for this work involves the use of microphones, loudspeakers, headphones and projection. Each of the acoustic musicians on stage has a condenser microphone and a separate headphone send for a click track.

fractional dimensions. This composition began as an exploration in musical structures, from fractal and infinite pitch series, fractal rhythmic structure, tempo canon, chaotic controlled spatialisation and audio feedback. The work ‘elaborates’ on the dimensionality of a small collection of simple musical structures in order to arrive at a more complex and immersive listening experience.

N-Dimension was a commission for the Decibel new music ensemble while I was involved in a week-long artist residency in the Perth Institute for Contemporary Arts. It is a work written for flute, bass clarinet, viola, cello, percussion and electronics. This is a chamber ensemble work that utilises multiple acoustic instruments processed in real time. Although it was performed and workshopped with eight speakers, it could be easily adapted for other speaker configurations. Other performances of this work were presented at the Audio Art Festival in Kraków, Poland, and the DIG Gallery in Košice, Slovakia, in 2013 and at ensemble Decibel’s Tuned Darker album launch at the Astor Theatre, Perth in 2015.

The technical setup for this work involves the use of microphones, loudspeakers, headphones and projection. Each of the acoustic musicians on stage has a condenser microphone and a separate headphone send for a click track.

The issue of synchronising the performance meant that multiple click tracks for the performers were necessary. The click track reflects these time proportions precisely. The tempo ratio between the flute, bass clarinet and percussion v. the cello is 5:6 and the tempo ratio between the flute, bass clarinet and percussion v. the viola is 4:5. This means the ratio between the viola and cello is 25:24. The tempos are rounded in the parts as they did not need to be represented as exact for the performers. These are 60 bpm (beats per minute) for the delay line; 67 bpm for the flute, bass clarinet and percussion; 80.5 bpm for the cello; and 84 bpm for the viola. The first section of the piece, though it does not feature multiple tempos, does have sections with no click instructing some performers to play more freely and at times semi-improvisatory, whereas other performers have a click and are required to perform a notated part strictly with the temporal grid.

The addition of video projection for ensemble Decibel’s launch of their album Tuned Darker involved visual artist and musician Karl Ockelford, who made visuals for the work using video of fluid kinematics ranging from cymatics to the chaotic and turbulent movement of water.

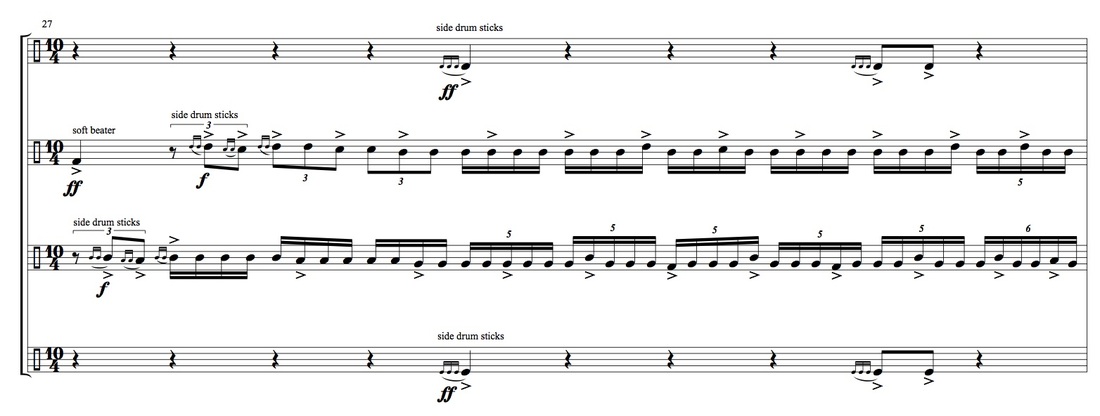

The composition is structured in two parts. The first section of the piece features a dialogue between horizontal pitch-based material and vertical non-pitched material. The horizontal pitch-based materials are derived through Per Nørgård’s infinite pitch series: the flute features fragments of a quarter-tone infinite series, and the other instruments feature a semi-tone infinite pitch series, starting from the same original pitch A. The percussion parts are derived using rhythms generated by Lindenmayer systems fractals. The fractal MIDI note generator in Figure 153a is an adaptation and extension to some of the Jitter example patches provided with MaxMSP. I extended these to support MIDI note generation and ported to Max4Live. These processes enabled the generation of the parts for the musicians. For example the Lindenmayer systems as shown in Figure 153a are used to derive the percussion shapes noted in Figure 153b.

The use of a tempo canon was inspired by a desire to view higher-dimensional objects in a lower-dimensional space; as these higher-dimensional objects rotate, their structure appears to transform and shift outside of their original geometric alignment. This notion was inspired when viewing hyper-dimensional objects in 3D space such as the simplex and some other more complex hyper-geometric objects. We cannot see the entirety of a higher-dimensional object in three dimensions unless we see it projected onto three dimensions or a two-dimensional plane. We can nonetheless observe these higher-dimensional geometries passing through our visible 3D space (Manning, 1990). Jonathan Kramer (1988) refers to this as a ‘timepoint’, or “an instant, analogous to a geometrical point in space” (p. 454). A timepoint has no dimension, as explained by Kramer:

Whereas a timespan is a specific duration (whether of a note, chord, silence, motive, or whatever), a timepoint really has no duration. We hear events that start or stop at timepoints, but we cannot hear the timepoints themselves. A timepoint is thus analogous to a point in geometric space. By definition, a point has no size: It is not a dot on the page, although a dot may be used to represent a point. Similarly, a staccato note or the attack of a longer note necessarily falls on and thus may represent a timepoint, but a timepoint in music is as inaudible as a geometric point is invisible. (Kramer 1988, pp. 82–83)

The strands of musical canon function in a similar way, finally converging in the closing musical statement melodically and rhythmically, and ultimately creating a sense of cadential resolve. The effect of convergence in the context of tempo canon is evident in the work of Conlon Nancarrow. Nancarrow’s tempo canons are perceptually heightened because they involve not only temporal convergence, but convergence of canonic material (Nemire, 2012). Margaret Thomas (1996) describes a palpable sense of the voices being in different places at the same time, of gradually moving closer together, of a brief moment of coordination and then a departure. The most characteristic structural feature of Nancarrow’s tempo canons is the convergence point, or “the infinitesimal moment at which all lines have reached identical points in the material they are playing” (Gann, 1995, p. 21). Thomas (1996) in fact describes this form of tempo canon as a converging canon, where the one primary convergence point comes at the very end.

The second half features use of isorhythm in the bass clarinet, viola and cello. Each instrumentalist has strands of the same melody, each note repeating seven times before moving to the next note, but with a different length tala rhythm. This melody is occasionally interrupted by a contraction or expansion in the length of the pitch repetitions causing these overlapping strains to shift, appearing to accelerate or decelerate as shown in Figure 154.

Most of the performed material in the flute, bass clarinet, viola and cello is sampled during the first section of the work, and processed using granular techniques. This method is used for collecting timbral colours and building tone clusters, as the granular instruments I built read from several different buffers of sound sampled at different points in time. This allows for the tone clusters that are captured to gradually morph and shift into the next. These samples also become the basis of material that accompanies the tempo canon in the second section of the work.

The electronics are managed with a cue list of instructions that determine when certain actions are to take place with respect to the click. These are stored in a series of coll objects with a timestamp referring to when they are to take place. As I was responsible for performing the electronics, this automation simplified the role to controlling the timbre spatialisation and the mix levels throughout the performance.

The spatialisation uses swarm-based techniques, timbre spatialisation and multi- tap delay. The use of the delay line in this early section of the work was considered while writing the score, each tap repeating a note around the listener area through different speakers. At the beginning of the work the delay is only applied to the percussion’s vertical non-pitched material. Gradually the delay line encroaches on the horizontal pitch-based material suggesting the use of canonic entries, displaced spatially across the listening space. The ever-increasing use of the delay line as applied to the entire ensemble ultimately leads to the second section of the work, a tempo canon. The repeated delay tap even suggests the seven-note repeats that are seen in the instrumental parts in the second section. The multi-tap delay line is responsible for re-articulating the same material at different points in time, and at different spatial positions. These are arranged in a crisscross configuration over the eight-channel speaker configuration as shown in Figure 155a. The fact that the delay line also has a fixed tempo contributes to the in- and out-of-phase nature of the different canonic layers, enhancing the impression of synchronisation v. out-of-synchronisation.

The swarm-based spatialisation is used on the flute clusters throughout the first section of the work. This spatialisation eventually fades out of the texture, and by the second section of the work, timbre spatialisation is applied to samples of the bass clarinet creating breath-like sounds, as well as the revisiting of a chord from the viola and cello earlier in the piece. The timbre spatialisation uses only a circular trajectory that is occasionally disturbed at the discretion of the laptop performer to inject low- frequency spatial texture. The terrain is used specifically here to derive the spectromorphology and spatiomorphology. The use of Voronoi surfaces creates non- linear contours (see Figure 155b) that are translated and morphed to create these waves of energy that envelop the audience. They are generated randomly, so these sound shapes emerge differently in each performance.

The addition of video projection for ensemble Decibel’s launch of their album Tuned Darker involved visual artist and musician Karl Ockelford, who made visuals for the work using video of fluid kinematics ranging from cymatics to the chaotic and turbulent movement of water.

The composition is structured in two parts. The first section of the piece features a dialogue between horizontal pitch-based material and vertical non-pitched material. The horizontal pitch-based materials are derived through Per Nørgård’s infinite pitch series: the flute features fragments of a quarter-tone infinite series, and the other instruments feature a semi-tone infinite pitch series, starting from the same original pitch A. The percussion parts are derived using rhythms generated by Lindenmayer systems fractals. The fractal MIDI note generator in Figure 153a is an adaptation and extension to some of the Jitter example patches provided with MaxMSP. I extended these to support MIDI note generation and ported to Max4Live. These processes enabled the generation of the parts for the musicians. For example the Lindenmayer systems as shown in Figure 153a are used to derive the percussion shapes noted in Figure 153b.

The use of a tempo canon was inspired by a desire to view higher-dimensional objects in a lower-dimensional space; as these higher-dimensional objects rotate, their structure appears to transform and shift outside of their original geometric alignment. This notion was inspired when viewing hyper-dimensional objects in 3D space such as the simplex and some other more complex hyper-geometric objects. We cannot see the entirety of a higher-dimensional object in three dimensions unless we see it projected onto three dimensions or a two-dimensional plane. We can nonetheless observe these higher-dimensional geometries passing through our visible 3D space (Manning, 1990). Jonathan Kramer (1988) refers to this as a ‘timepoint’, or “an instant, analogous to a geometrical point in space” (p. 454). A timepoint has no dimension, as explained by Kramer:

Whereas a timespan is a specific duration (whether of a note, chord, silence, motive, or whatever), a timepoint really has no duration. We hear events that start or stop at timepoints, but we cannot hear the timepoints themselves. A timepoint is thus analogous to a point in geometric space. By definition, a point has no size: It is not a dot on the page, although a dot may be used to represent a point. Similarly, a staccato note or the attack of a longer note necessarily falls on and thus may represent a timepoint, but a timepoint in music is as inaudible as a geometric point is invisible. (Kramer 1988, pp. 82–83)

The strands of musical canon function in a similar way, finally converging in the closing musical statement melodically and rhythmically, and ultimately creating a sense of cadential resolve. The effect of convergence in the context of tempo canon is evident in the work of Conlon Nancarrow. Nancarrow’s tempo canons are perceptually heightened because they involve not only temporal convergence, but convergence of canonic material (Nemire, 2012). Margaret Thomas (1996) describes a palpable sense of the voices being in different places at the same time, of gradually moving closer together, of a brief moment of coordination and then a departure. The most characteristic structural feature of Nancarrow’s tempo canons is the convergence point, or “the infinitesimal moment at which all lines have reached identical points in the material they are playing” (Gann, 1995, p. 21). Thomas (1996) in fact describes this form of tempo canon as a converging canon, where the one primary convergence point comes at the very end.

The second half features use of isorhythm in the bass clarinet, viola and cello. Each instrumentalist has strands of the same melody, each note repeating seven times before moving to the next note, but with a different length tala rhythm. This melody is occasionally interrupted by a contraction or expansion in the length of the pitch repetitions causing these overlapping strains to shift, appearing to accelerate or decelerate as shown in Figure 154.

Most of the performed material in the flute, bass clarinet, viola and cello is sampled during the first section of the work, and processed using granular techniques. This method is used for collecting timbral colours and building tone clusters, as the granular instruments I built read from several different buffers of sound sampled at different points in time. This allows for the tone clusters that are captured to gradually morph and shift into the next. These samples also become the basis of material that accompanies the tempo canon in the second section of the work.

The electronics are managed with a cue list of instructions that determine when certain actions are to take place with respect to the click. These are stored in a series of coll objects with a timestamp referring to when they are to take place. As I was responsible for performing the electronics, this automation simplified the role to controlling the timbre spatialisation and the mix levels throughout the performance.

The spatialisation uses swarm-based techniques, timbre spatialisation and multi- tap delay. The use of the delay line in this early section of the work was considered while writing the score, each tap repeating a note around the listener area through different speakers. At the beginning of the work the delay is only applied to the percussion’s vertical non-pitched material. Gradually the delay line encroaches on the horizontal pitch-based material suggesting the use of canonic entries, displaced spatially across the listening space. The ever-increasing use of the delay line as applied to the entire ensemble ultimately leads to the second section of the work, a tempo canon. The repeated delay tap even suggests the seven-note repeats that are seen in the instrumental parts in the second section. The multi-tap delay line is responsible for re-articulating the same material at different points in time, and at different spatial positions. These are arranged in a crisscross configuration over the eight-channel speaker configuration as shown in Figure 155a. The fact that the delay line also has a fixed tempo contributes to the in- and out-of-phase nature of the different canonic layers, enhancing the impression of synchronisation v. out-of-synchronisation.

The swarm-based spatialisation is used on the flute clusters throughout the first section of the work. This spatialisation eventually fades out of the texture, and by the second section of the work, timbre spatialisation is applied to samples of the bass clarinet creating breath-like sounds, as well as the revisiting of a chord from the viola and cello earlier in the piece. The timbre spatialisation uses only a circular trajectory that is occasionally disturbed at the discretion of the laptop performer to inject low- frequency spatial texture. The terrain is used specifically here to derive the spectromorphology and spatiomorphology. The use of Voronoi surfaces creates non- linear contours (see Figure 155b) that are translated and morphed to create these waves of energy that envelop the audience. They are generated randomly, so these sound shapes emerge differently in each performance.

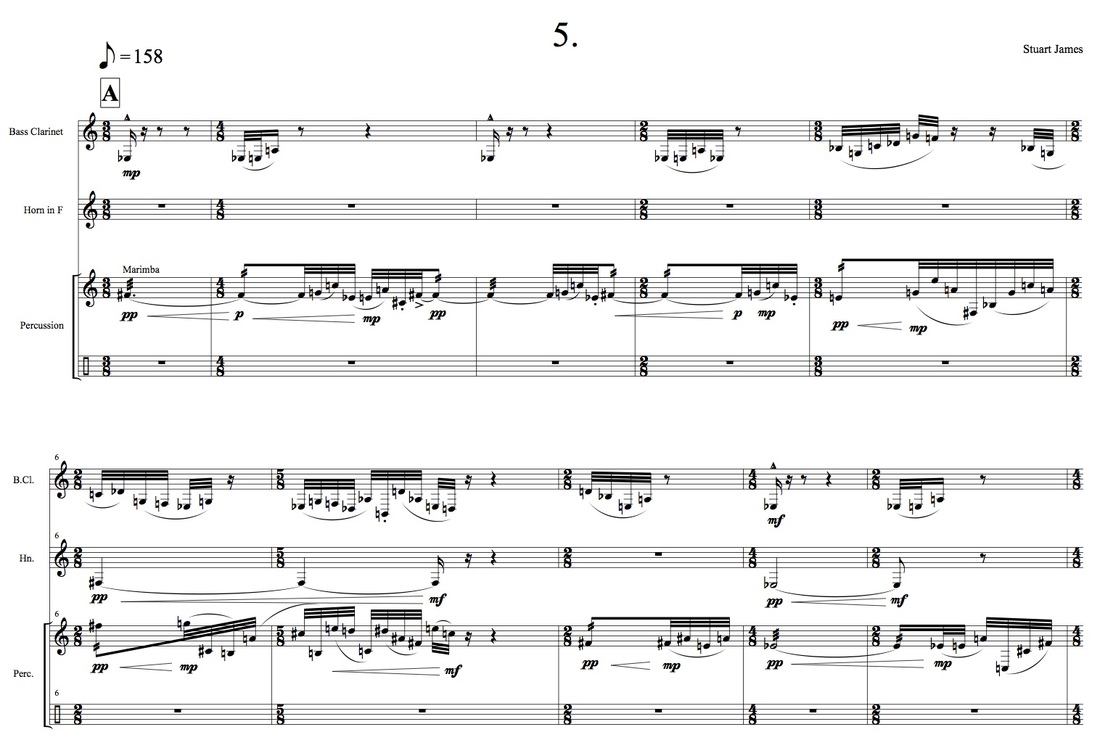

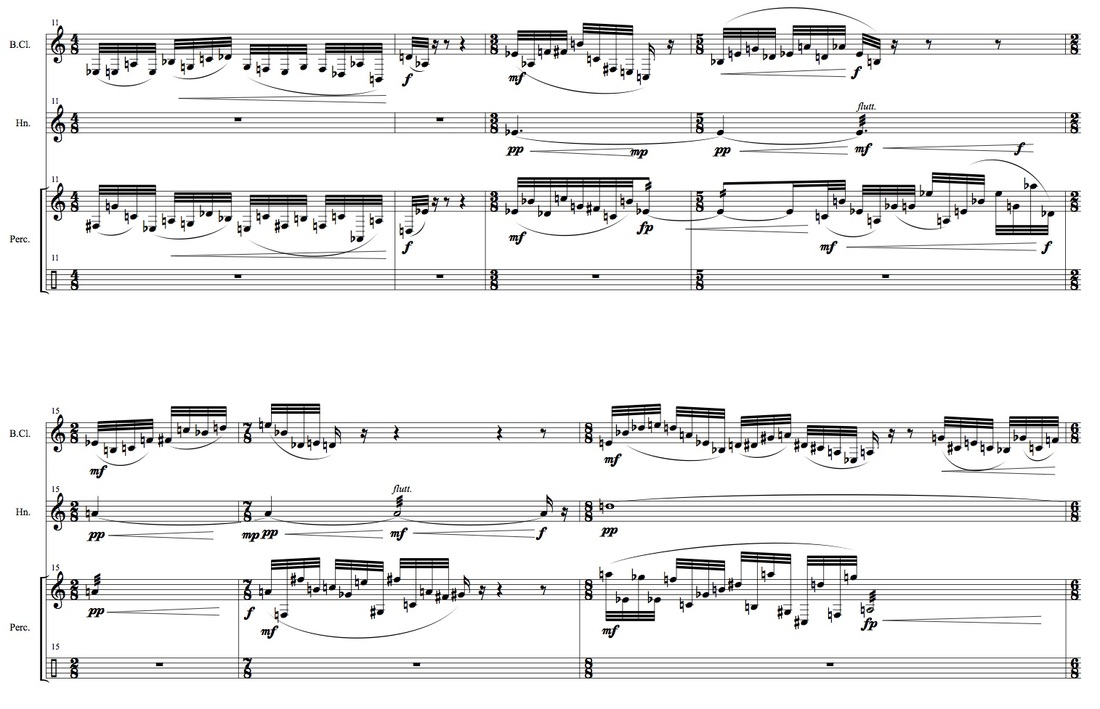

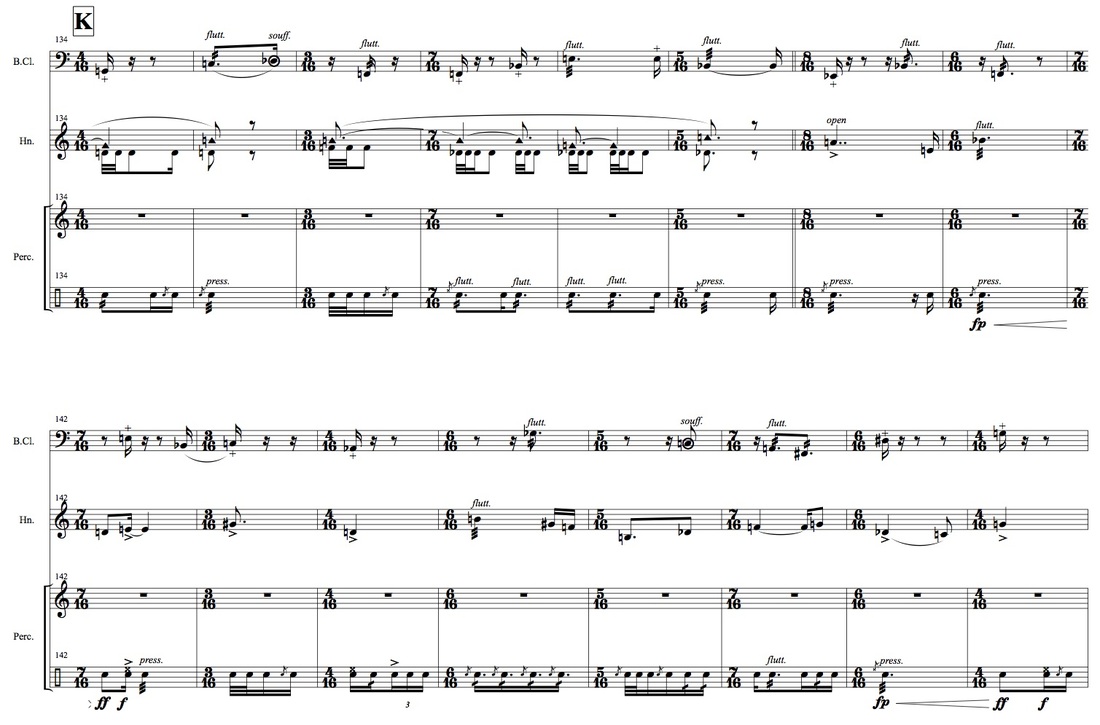

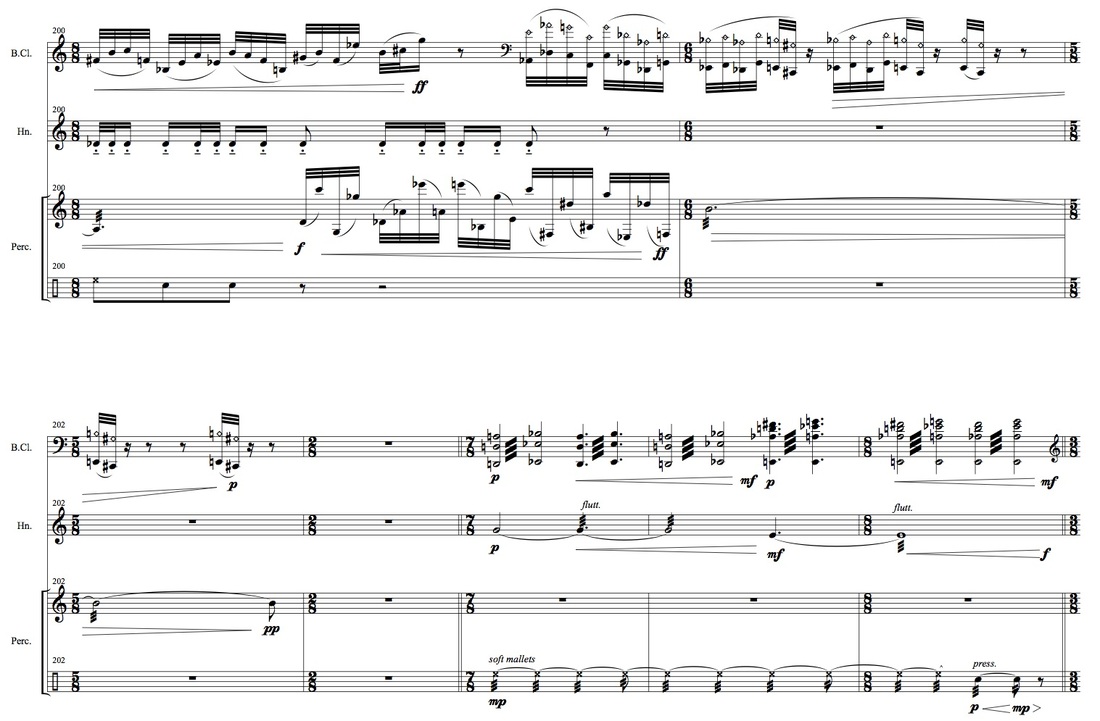

5 (2003)

For Bass Clarinet, French Horn, and Percussion (commissioned by the ABC).

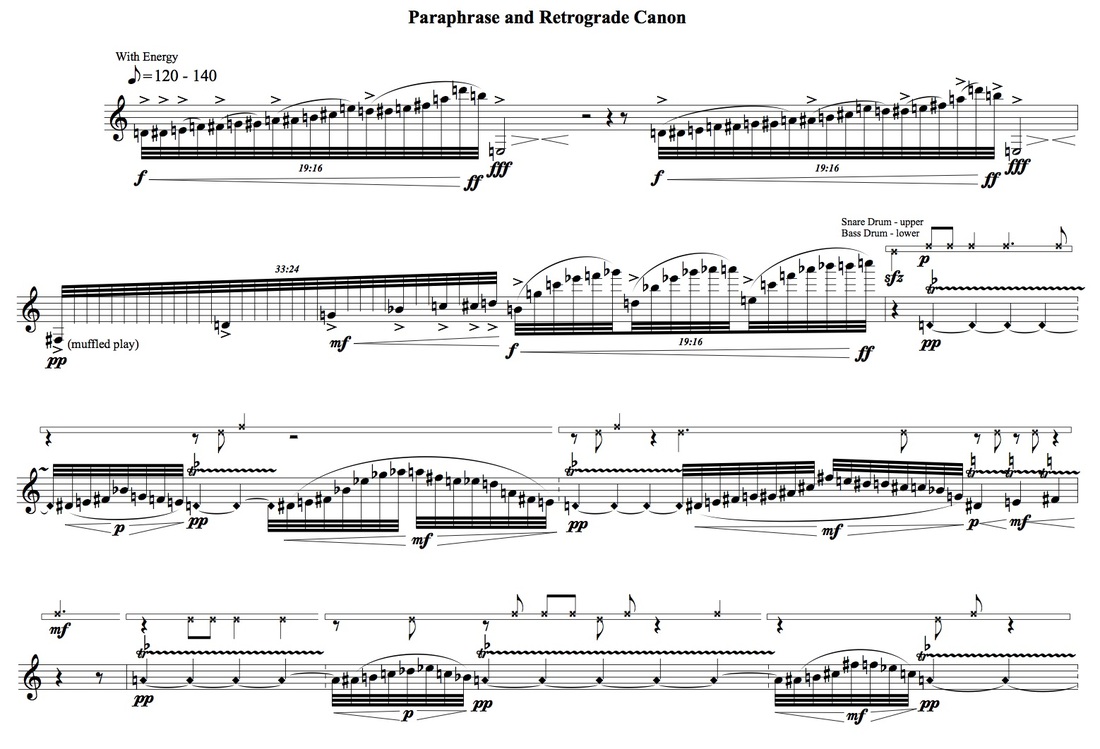

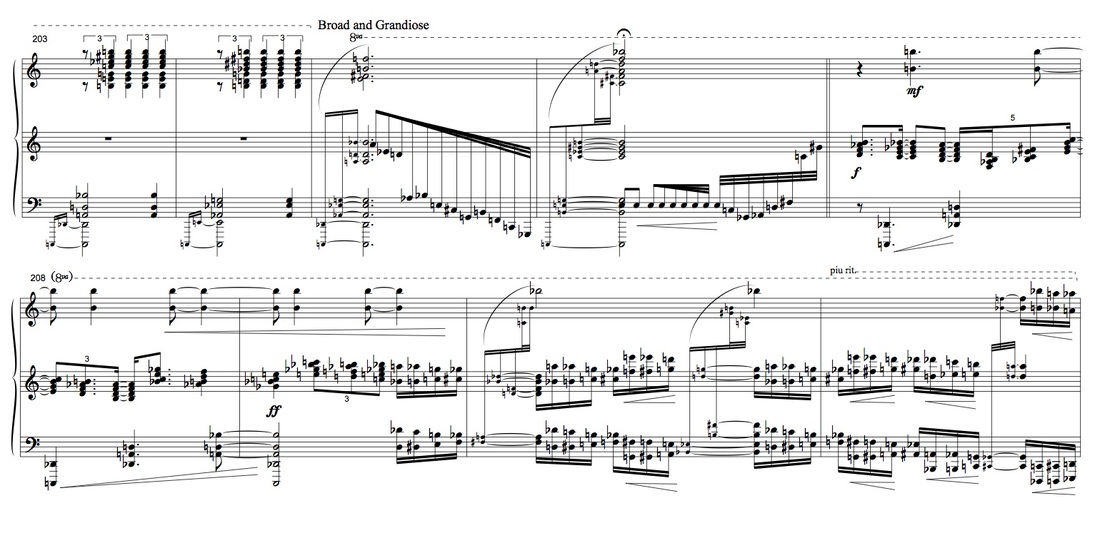

Based on an extract from Roger Smalley's Piano Concerto, this piece treats the theme in a variety of ways in order to create a piece intended to be fast, manic, and virtuosic. Without the original sentiment of the theme, this piece transforms the original into a highly strung game of rhythmic, melodic, and structural counterpoint that concludes in a rampant display of frantic activity.

Noctis Labyrinthus: a labyrintho opaco ad occidentalem montem ultra martem (2003)

For Chamber Orchestra (commissioned by the ABC).

English translation - the labyrinth of the night: from [away from] the overshadowed [mysterious] labyrinth toward the Western mountain on the far [other] side of Mars

Duration: circa 12 minutes

(1) Noctis Labyrinthus

(2) Tharsis Plain

(3) Ascraeus Mons

"...an effective essay in musical abstraction with intriguing use of, among other devices, the clicking of woodwind keys and the audible bleathiness of blowing into brass mouthpieces."

Neville Cohn, The West Australian (2002)

The Noctis Labyrinthus is a geological formation found on Mars consisting of a complex series of intersecting valleys, canyons, cliffs, and steep rocky terrain. In addition to the inherent instability of the physical structures throughout this region, the Noctis Labyrinthus is perpetually engulfed by dust cloud. These elements have sparked off, for many people, mysterious and mythical connotation. Further west of the Noctis Labyrinthus can be found the Tharsis Dome, a relatively flat region that stretches for two-thousand miles, and which holds home to the Tharsis Montes, some of the most massive volcanoes in our solar system. One of these volcanoes is the Ascraeus Mons: a shield volcano 11 kilometers tall and 450 kilometers in diameter, with a structure that appears to have collapsed at various points due to physical stress.

Despite integral structural elements, the piece remains predominantly "visual" since the piece describes a programmatical journey from the Noctis Labyrinthus, then westward toward the Ascraeus Mons over the Tharsis plain. Certain other musical attributions are made throughout the piece. Firstly, the pitch D has been coupled to the planet Mars, an association that Nichomachus proposes in his Excerpta 3 (2nd Century AD). The use of two ancient greek 10-note melodies found on two different papyrus fragments similarly remain integral: Hymn to Asclepius and the Berlin Papyrus 6870, line 23. Furthermore, the use of numerology and the Mars "magic square" have assisted to develop tonal possibilities. Lastly, the piece is divided, at times, according to ancient greek rhythmic mode: Dactylic, Iambic, Paeonic, Dochmaic, and Ionic.

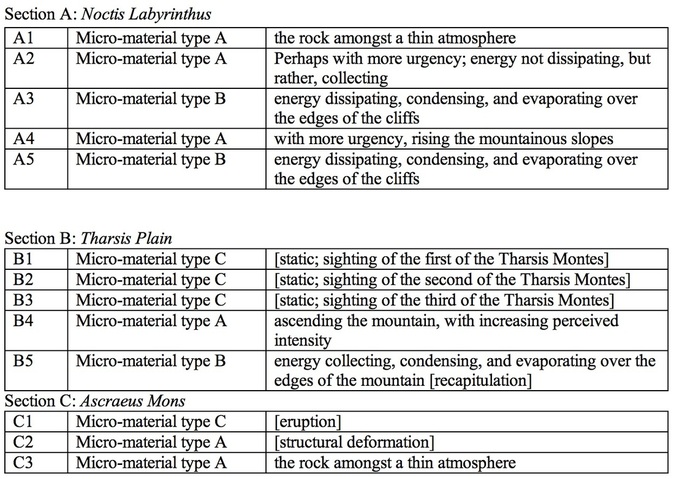

The structure also follows a more involved musical structure that is defined by three different criteria. The first of these structures represent physical space (i.e. solid, liquid, air). These sections gradually undergo a metamorphosis from a reasonably stable texture to one that is more complex. The second types of material represent transitions in physical state (i.e. condensation, evaporation), and these subsections are characterized by more detailed textures. The third type represents material that is to be associated with the eruption of the volcano (i.e. re-occurrences of the ancient greek melodies) and the complex combinations and changes of physical state that may be present at any one time during a high-energy event.

Duration: circa 12 minutes

(1) Noctis Labyrinthus

(2) Tharsis Plain

(3) Ascraeus Mons

"...an effective essay in musical abstraction with intriguing use of, among other devices, the clicking of woodwind keys and the audible bleathiness of blowing into brass mouthpieces."

Neville Cohn, The West Australian (2002)

The Noctis Labyrinthus is a geological formation found on Mars consisting of a complex series of intersecting valleys, canyons, cliffs, and steep rocky terrain. In addition to the inherent instability of the physical structures throughout this region, the Noctis Labyrinthus is perpetually engulfed by dust cloud. These elements have sparked off, for many people, mysterious and mythical connotation. Further west of the Noctis Labyrinthus can be found the Tharsis Dome, a relatively flat region that stretches for two-thousand miles, and which holds home to the Tharsis Montes, some of the most massive volcanoes in our solar system. One of these volcanoes is the Ascraeus Mons: a shield volcano 11 kilometers tall and 450 kilometers in diameter, with a structure that appears to have collapsed at various points due to physical stress.

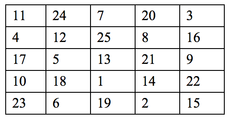

Despite integral structural elements, the piece remains predominantly "visual" since the piece describes a programmatical journey from the Noctis Labyrinthus, then westward toward the Ascraeus Mons over the Tharsis plain. Certain other musical attributions are made throughout the piece. Firstly, the pitch D has been coupled to the planet Mars, an association that Nichomachus proposes in his Excerpta 3 (2nd Century AD). The use of two ancient greek 10-note melodies found on two different papyrus fragments similarly remain integral: Hymn to Asclepius and the Berlin Papyrus 6870, line 23. Furthermore, the use of numerology and the Mars "magic square" have assisted to develop tonal possibilities. Lastly, the piece is divided, at times, according to ancient greek rhythmic mode: Dactylic, Iambic, Paeonic, Dochmaic, and Ionic.

The structure also follows a more involved musical structure that is defined by three different criteria. The first of these structures represent physical space (i.e. solid, liquid, air). These sections gradually undergo a metamorphosis from a reasonably stable texture to one that is more complex. The second types of material represent transitions in physical state (i.e. condensation, evaporation), and these subsections are characterized by more detailed textures. The third type represents material that is to be associated with the eruption of the volcano (i.e. re-occurrences of the ancient greek melodies) and the complex combinations and changes of physical state that may be present at any one time during a high-energy event.

THE MUSICAL CREATIVE PROCESS AND THE NOCTIS LABYRINTHUS

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a ‘labyrinth’ as a “…structure consisting of a number of intercommunicating passages arranged in bewildering complexity, through which it is difficult or impossible to find one’s way without guidance.” (The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Ed., Vol. VIII (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), p564).

There appears to have been a significant difference in opinion regarding a generalised interpretation and understanding of the evolution and manifestation of ideas pertaining to the creative process in the field of music composition. Superficially it might seem as though such statements fall into two opposing categories of thought: those statements that have attracted blatant contradiction to other seemingly, yet equally, valid opinions; and those similarities of opinion that might converge, due to the influence of certain dominating schools of thought, culture, and tradition.

New music doesn’t automatically appear by merely writing notes on paper – it occurs through prolonged deliberation about the substances of music, and the highly conscious imposition on them of new modes of thought. Music demands a constant renewal of language….[1]

As a response, in 1968, to what was really an embarrassing – and in his own words, rather boring – definition of ‘modern’ music, Roger Smalley retorted by striking at the heart of the role of the composer-musician. The creative process is, as described here, a careful weighing of merits of various musical substance, with full, intentional, and unhurried consideration. Once this is achieved, new ideas may be developed by the composer based on their refined understanding of the Western musical heritage. It seems that the emphasis here is of a conscious approach to the creative process. An approach which, within the context of Smalley's article, is favored by many streams of twentieth century compositional practice, particularly those devoted to deterministic processes and paradigms of thought. In parallel to the idealogical positivism associated with the industrial revolution was a trend toward systematic methodology. Musicologists and ethnomusicologists then relied on systematic and formal analysis techniques alongside historiographical accounts to explain or support discussions on the inner meaning of music and the way in which it works. In certain streams of music, compositional practice also appeared to follow a trend toward systematic processes too.

One only has to turn back to 1911 to find a statement that is the complete antithesis of what Smalley was to write over fifty years later.

…art belongs to the unconscious! One must express oneself! Express oneself directly! Not one’s taste or one’s upbringing, or one’s intelligence, knowledge or skill. Not all these acquiredcharacteristics, but that which is inborn, instinctive.[2]

It was Arnold Schoenberg, in his candid letter to the painter Wallisy Kandinsky, who expressed these creative ideals. This was through a period that is now recognized as his expressionist phase, when Schoenberg was seeking out a mode of self-expression that did not rely on one’s own training, nor upon any conscious process, but rather an approach that could be understood, in a sense, as a reflection of the essence of ones own primeval ontology. With the development of Freudian psychoanalysis, it is not so surprising that active discourse did arise, due to healthy curiosity in both the notion of the pre-conscious and the subconscious mind. Ironically, however, it was Schoenberg himself who, only a year later, began to drift away from these instinctive ideals in favor of a constructivist and modernist approach to music composition. After turning away from a process governed by intuition, he was to define one of the key aspects of what was to later become a significant ingredient in modernist Avant Garde musical thought: serialism, and the road toward the parametrisation of music.

On the contrary, Sir Harrison Birtwistle (1934-) doesn’t seem to agree with either of these creative ideals entirely:

You see, I think the problem of talking about creativity is that there’s always this idea that the creator is absolutely in control and can answer everything all the way down the line. I don’t think that’s so. I think you’re in control of a certain number of things, and there are also things which happen, which are not accidents, they’re things which are thrown up by context. It’s a bit like making two buildings. You build one here and another one 200 yards down. And they obey certain principles, but what we didn’t take into consideration is the space between the two buildings, and what’s going to be a view from, say, a mile away – we didn’t consider those things.[3]

Birtwistle explains that once one becomes the victim of a pre-compositional structure, one inevitably becomes a slave to the process. He suggests that this is like making methods of composition outside the context of a piece. Secondly, he expresses a mistrust of intuition, believing that it produces only clichés. The creative process for Birtwistle begins with the writing down of an idea until he is satisfied that a context is established. From here, he investigates the idea before creatively elaborating upon the structural basis and context that was initially suggested.

Despite significant recognition as part of the modernist generation of composers, Birtwistle maintains his protest against the pre-compositional structural process. Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (1934-), on the other hand, maintains his own production of extensive pre-compositional workings formulating macrostructure and microstructure. It seems that, even though these composers are of the same generation, they have completely different ideas about the compositional process.

So surely for most composers – if not all – the creative process would remain highly subjective, since each composer will invariably have their own artistic ideals and needs with regard to the exploration of "creative curiosities." These ideals may indeed also evolve through the course of a composers' own career, as can be traced across the lifespan of various composers: Beethoven and Stravinsky are often said to have three significant periods that outline their creative journeys. Creative ideals may indeed also change during the course of writing a single work too.

Perhaps any generalization of the creative process is prone to flaw. Newer ideologies of postmodernist thought have seen a growing acceptance of "anything goes" presenting composers with significantly more freedoms along with an acceptance of music right across the canon of Western Art Music and beyond. The challenge for the postmodernist composer is to be sure about the direction of their endeavour. The ship can sail in 360 degrees, but a sense of conviction, making a firm decision, and setting off course is needed. It is vital the composer describes a sense of intentionality with respect to their own work, and whether this is conceived intuitively, determinately, or using indeterminate processes is hardly the point. What is more the point is that if the composer is presented with the possibility of "all of the possible options", the task is rather like navigating a complex web of options, a labyrinth, that is forever dependent on the nature of how the musical situation unfolds. In an interview, Birtwistle was asked whether his entire musical output was like one big labyrinth; he replied: “Yes, that’s right. That’s right. That is conscious.”[4]

The first stage in the creative process is, no doubt, the realization of an idea. This is the initial spark, or revelation. This idea might exist in a variety of guises. The idea may have been triggered by an event, perhaps inspired, or maybe not. This idea could be musical, or non-musical. The idea may have arisen through some sort of artistic opportunity. The main principle is that this initial planting of a seed provides a context for future endeavor. That it promises a worthy and enlightening journey. A starting point from which a greater understanding can be built. A context from which an idea can grow.

Is his basic instinct directed towards art, or is it not rather directed towards the meaning of art, which is life? Art is the great stimulus to life: how could it be thought purposeless, aimless, l’artpour l’art?[5]

The second stage deals with the development of an initial idea. This could involve processes of brainstorming, research, structural elaboration, experimentation, and planning, relevant discourse with other practitioners, the consideration of ones main sense of purpose, consideration of ones own musical aims, the relative significance of the planned piece, consideration of performers, performance space, instrumentation, duration, and musical substance. Most importantly, it is a process that deals with the intoxication of ideas for the purposes of reaching a manifestation of the main idea.

For art to exist, for any sort of aesthetic activity or perception to exist, a certain physiological precondition is indispensable: intoxication. … From out of this feeling one gives to things, onecompels them to take….[6]

The point at which one might reach this manifestation cannot be judged temporally, so the journey may often remain not entirely clear or known. A multiplicity of multifarious ideas converge in this process, perhaps even only linked together by the initial idea. Again the analogy of sailing a ship might be appropriate in the sense that, whilst the destination is beyond the horizon, there must be a conviction in the direction of sail to achieve the final outcome, and the composer needs to use the elements of music in a particular kind of conceived balance in order to arrive at this outcome. This process could be related synonymously to the exploration of the labyrinth. The labyrinth of ideas. Only at some unknowing point in time does it become clear how to proceed.

In many ways, the third and fourth stages go hand in hand. The third deals with the setting of boundaries and restrictions, and the fourth deals with the actual composition of the piece itself.

The setting of boundaries essentially deals with a set of rules governing the act of composition. These rules determine the amount of elasticity one has over the work. This process is concerned with the design of the key working systems, i.e. macrostructure and/or microstructure. For example, Birtwistle uses concepts of a foreground, middle-ground, and background to govern his musical space:

One thing that I do seek is…a musical foreground – something that speaks to the surface of the piece. It’s not two dimensional. Once you have a foreground, then you have a middle ground and a background – you have depth, you have something you can go into. That way you can have complexity. I don’t think you can have complexity in a situation where it’s all complex, or all thick, because it’s all of the same order….[7]

The act of composing the piece deals directly with the writing of all musical material, more often than not at a micro-material level. Obviously the ultimate aim of this process is the completion of the piece. However, in order to fulfill this, one often may need a great passion for their work; a sense of passion that is required for a sustained faith in the unifying idea.

The passion is necessary: …an art, does not have as its object the commonplace and the trivial, the valueless. It attaches itself to actions in which the characters have an investment, situations in which they venture their lives and their feelings, their moral and their political choices: their passions! What is a passion? It is a feeling for someone or something, or an idea, that we prize more highly than our own life.[8]

Again, a labyrinth can depict the creative process, but this time it represents the context associated with the composing of the musical score. During this process, it is not difficult to be distracted by the multitude of possibilities. One hopes that the structural and pre-compositional planning may provide a guiding light for these situations.

The fifth stage is concerned with the rehearsal of the work. This process involves the typesetting of parts in a way that must communicate the score as clearly as possible; a valuable practice that saves time and explanation during rehearsal. It may also be necessary to address any technical oversights that might exist within the performance parts. And depending on the situation, it is certainly possible that one may have to mediate through a conductor, rather than dealing with the ensemble directly.

The last stage is the performance. It is only through the performance of a work that an idea suddenly takes on a new form. A sonic form with which a potential audience can respond. It is from here that the work moves into the domain of experience, consciousness, and perception outside of the world of the artist. The work has been given an opportunity to exist.

Is it possible for an audience, however, whilst experiencing a new and ‘alien’ piece of music, to experience this unfolding of the labyrinth - this very conscious experience by the composer writing the work from beginning to end, deliberately conscious of this metaphor. It is unlikely, nevertheless those that did experience the work expressed a sense of the music emerging from nebula-like clouds of sound. The latter sections of the piece are also contrasted with a sense of clarity and austerity and power.

Initial Idea

The originating idea for this piece was not an inspired moment, nor the revelation of an idea. Quite simply, it seemed appropriate for me, as a young composer, to further myself in my compositional capacity, by writing a work for the West Australian Symphony Orchestra’s New Music Ensemble. It was after approaching Roger Smalley in Jan 2002 about this possibility that the opportunity came about.

Development of the Idea & Pre-Compositional Working

The pre-compositional working for Noctis Labyrinthus developed over the course of about five months. Initially I was preoccupied by compositional structures that might result in interesting, and quite possibly hidden, relationships. The first sketches dealt with a systematic approach of transposing lines of melodic material within transpositional matrices for use as pitch-class series. At some point it seemed appropriate for me to be using fragments of ancient greek melody, since I had been curious about Ancient Greek Music theory for some years, and had developed a fascination with musical traditions that had disappeared long ago. The idea that many of these ancient systems approached music in a way that would be considered quite foreign to us now had great appeal to me. I selected melodies that presented unusual melodic contours, which I transposed according to a transpositional matrix with the expectation of finding some unusual and interesting harmonic possibilities.

Through my reading of Peter Maxwell Davies in previous years, I decided to use, as he had done, a renaissance astrological “magic square” for the pre-compositional working. Davies used these mathematical formations to re-order series of pitch-class sets according to the special numerical order of the “magic square.”

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a ‘labyrinth’ as a “…structure consisting of a number of intercommunicating passages arranged in bewildering complexity, through which it is difficult or impossible to find one’s way without guidance.” (The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Ed., Vol. VIII (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), p564).

There appears to have been a significant difference in opinion regarding a generalised interpretation and understanding of the evolution and manifestation of ideas pertaining to the creative process in the field of music composition. Superficially it might seem as though such statements fall into two opposing categories of thought: those statements that have attracted blatant contradiction to other seemingly, yet equally, valid opinions; and those similarities of opinion that might converge, due to the influence of certain dominating schools of thought, culture, and tradition.

New music doesn’t automatically appear by merely writing notes on paper – it occurs through prolonged deliberation about the substances of music, and the highly conscious imposition on them of new modes of thought. Music demands a constant renewal of language….[1]

As a response, in 1968, to what was really an embarrassing – and in his own words, rather boring – definition of ‘modern’ music, Roger Smalley retorted by striking at the heart of the role of the composer-musician. The creative process is, as described here, a careful weighing of merits of various musical substance, with full, intentional, and unhurried consideration. Once this is achieved, new ideas may be developed by the composer based on their refined understanding of the Western musical heritage. It seems that the emphasis here is of a conscious approach to the creative process. An approach which, within the context of Smalley's article, is favored by many streams of twentieth century compositional practice, particularly those devoted to deterministic processes and paradigms of thought. In parallel to the idealogical positivism associated with the industrial revolution was a trend toward systematic methodology. Musicologists and ethnomusicologists then relied on systematic and formal analysis techniques alongside historiographical accounts to explain or support discussions on the inner meaning of music and the way in which it works. In certain streams of music, compositional practice also appeared to follow a trend toward systematic processes too.

One only has to turn back to 1911 to find a statement that is the complete antithesis of what Smalley was to write over fifty years later.

…art belongs to the unconscious! One must express oneself! Express oneself directly! Not one’s taste or one’s upbringing, or one’s intelligence, knowledge or skill. Not all these acquiredcharacteristics, but that which is inborn, instinctive.[2]

It was Arnold Schoenberg, in his candid letter to the painter Wallisy Kandinsky, who expressed these creative ideals. This was through a period that is now recognized as his expressionist phase, when Schoenberg was seeking out a mode of self-expression that did not rely on one’s own training, nor upon any conscious process, but rather an approach that could be understood, in a sense, as a reflection of the essence of ones own primeval ontology. With the development of Freudian psychoanalysis, it is not so surprising that active discourse did arise, due to healthy curiosity in both the notion of the pre-conscious and the subconscious mind. Ironically, however, it was Schoenberg himself who, only a year later, began to drift away from these instinctive ideals in favor of a constructivist and modernist approach to music composition. After turning away from a process governed by intuition, he was to define one of the key aspects of what was to later become a significant ingredient in modernist Avant Garde musical thought: serialism, and the road toward the parametrisation of music.

On the contrary, Sir Harrison Birtwistle (1934-) doesn’t seem to agree with either of these creative ideals entirely:

You see, I think the problem of talking about creativity is that there’s always this idea that the creator is absolutely in control and can answer everything all the way down the line. I don’t think that’s so. I think you’re in control of a certain number of things, and there are also things which happen, which are not accidents, they’re things which are thrown up by context. It’s a bit like making two buildings. You build one here and another one 200 yards down. And they obey certain principles, but what we didn’t take into consideration is the space between the two buildings, and what’s going to be a view from, say, a mile away – we didn’t consider those things.[3]

Birtwistle explains that once one becomes the victim of a pre-compositional structure, one inevitably becomes a slave to the process. He suggests that this is like making methods of composition outside the context of a piece. Secondly, he expresses a mistrust of intuition, believing that it produces only clichés. The creative process for Birtwistle begins with the writing down of an idea until he is satisfied that a context is established. From here, he investigates the idea before creatively elaborating upon the structural basis and context that was initially suggested.

Despite significant recognition as part of the modernist generation of composers, Birtwistle maintains his protest against the pre-compositional structural process. Sir Peter Maxwell Davies (1934-), on the other hand, maintains his own production of extensive pre-compositional workings formulating macrostructure and microstructure. It seems that, even though these composers are of the same generation, they have completely different ideas about the compositional process.

So surely for most composers – if not all – the creative process would remain highly subjective, since each composer will invariably have their own artistic ideals and needs with regard to the exploration of "creative curiosities." These ideals may indeed also evolve through the course of a composers' own career, as can be traced across the lifespan of various composers: Beethoven and Stravinsky are often said to have three significant periods that outline their creative journeys. Creative ideals may indeed also change during the course of writing a single work too.

Perhaps any generalization of the creative process is prone to flaw. Newer ideologies of postmodernist thought have seen a growing acceptance of "anything goes" presenting composers with significantly more freedoms along with an acceptance of music right across the canon of Western Art Music and beyond. The challenge for the postmodernist composer is to be sure about the direction of their endeavour. The ship can sail in 360 degrees, but a sense of conviction, making a firm decision, and setting off course is needed. It is vital the composer describes a sense of intentionality with respect to their own work, and whether this is conceived intuitively, determinately, or using indeterminate processes is hardly the point. What is more the point is that if the composer is presented with the possibility of "all of the possible options", the task is rather like navigating a complex web of options, a labyrinth, that is forever dependent on the nature of how the musical situation unfolds. In an interview, Birtwistle was asked whether his entire musical output was like one big labyrinth; he replied: “Yes, that’s right. That’s right. That is conscious.”[4]

The first stage in the creative process is, no doubt, the realization of an idea. This is the initial spark, or revelation. This idea might exist in a variety of guises. The idea may have been triggered by an event, perhaps inspired, or maybe not. This idea could be musical, or non-musical. The idea may have arisen through some sort of artistic opportunity. The main principle is that this initial planting of a seed provides a context for future endeavor. That it promises a worthy and enlightening journey. A starting point from which a greater understanding can be built. A context from which an idea can grow.

Is his basic instinct directed towards art, or is it not rather directed towards the meaning of art, which is life? Art is the great stimulus to life: how could it be thought purposeless, aimless, l’artpour l’art?[5]

The second stage deals with the development of an initial idea. This could involve processes of brainstorming, research, structural elaboration, experimentation, and planning, relevant discourse with other practitioners, the consideration of ones main sense of purpose, consideration of ones own musical aims, the relative significance of the planned piece, consideration of performers, performance space, instrumentation, duration, and musical substance. Most importantly, it is a process that deals with the intoxication of ideas for the purposes of reaching a manifestation of the main idea.

For art to exist, for any sort of aesthetic activity or perception to exist, a certain physiological precondition is indispensable: intoxication. … From out of this feeling one gives to things, onecompels them to take….[6]

The point at which one might reach this manifestation cannot be judged temporally, so the journey may often remain not entirely clear or known. A multiplicity of multifarious ideas converge in this process, perhaps even only linked together by the initial idea. Again the analogy of sailing a ship might be appropriate in the sense that, whilst the destination is beyond the horizon, there must be a conviction in the direction of sail to achieve the final outcome, and the composer needs to use the elements of music in a particular kind of conceived balance in order to arrive at this outcome. This process could be related synonymously to the exploration of the labyrinth. The labyrinth of ideas. Only at some unknowing point in time does it become clear how to proceed.

In many ways, the third and fourth stages go hand in hand. The third deals with the setting of boundaries and restrictions, and the fourth deals with the actual composition of the piece itself.

The setting of boundaries essentially deals with a set of rules governing the act of composition. These rules determine the amount of elasticity one has over the work. This process is concerned with the design of the key working systems, i.e. macrostructure and/or microstructure. For example, Birtwistle uses concepts of a foreground, middle-ground, and background to govern his musical space:

One thing that I do seek is…a musical foreground – something that speaks to the surface of the piece. It’s not two dimensional. Once you have a foreground, then you have a middle ground and a background – you have depth, you have something you can go into. That way you can have complexity. I don’t think you can have complexity in a situation where it’s all complex, or all thick, because it’s all of the same order….[7]

The act of composing the piece deals directly with the writing of all musical material, more often than not at a micro-material level. Obviously the ultimate aim of this process is the completion of the piece. However, in order to fulfill this, one often may need a great passion for their work; a sense of passion that is required for a sustained faith in the unifying idea.

The passion is necessary: …an art, does not have as its object the commonplace and the trivial, the valueless. It attaches itself to actions in which the characters have an investment, situations in which they venture their lives and their feelings, their moral and their political choices: their passions! What is a passion? It is a feeling for someone or something, or an idea, that we prize more highly than our own life.[8]

Again, a labyrinth can depict the creative process, but this time it represents the context associated with the composing of the musical score. During this process, it is not difficult to be distracted by the multitude of possibilities. One hopes that the structural and pre-compositional planning may provide a guiding light for these situations.

The fifth stage is concerned with the rehearsal of the work. This process involves the typesetting of parts in a way that must communicate the score as clearly as possible; a valuable practice that saves time and explanation during rehearsal. It may also be necessary to address any technical oversights that might exist within the performance parts. And depending on the situation, it is certainly possible that one may have to mediate through a conductor, rather than dealing with the ensemble directly.

The last stage is the performance. It is only through the performance of a work that an idea suddenly takes on a new form. A sonic form with which a potential audience can respond. It is from here that the work moves into the domain of experience, consciousness, and perception outside of the world of the artist. The work has been given an opportunity to exist.

Is it possible for an audience, however, whilst experiencing a new and ‘alien’ piece of music, to experience this unfolding of the labyrinth - this very conscious experience by the composer writing the work from beginning to end, deliberately conscious of this metaphor. It is unlikely, nevertheless those that did experience the work expressed a sense of the music emerging from nebula-like clouds of sound. The latter sections of the piece are also contrasted with a sense of clarity and austerity and power.

Initial Idea

The originating idea for this piece was not an inspired moment, nor the revelation of an idea. Quite simply, it seemed appropriate for me, as a young composer, to further myself in my compositional capacity, by writing a work for the West Australian Symphony Orchestra’s New Music Ensemble. It was after approaching Roger Smalley in Jan 2002 about this possibility that the opportunity came about.

Development of the Idea & Pre-Compositional Working

The pre-compositional working for Noctis Labyrinthus developed over the course of about five months. Initially I was preoccupied by compositional structures that might result in interesting, and quite possibly hidden, relationships. The first sketches dealt with a systematic approach of transposing lines of melodic material within transpositional matrices for use as pitch-class series. At some point it seemed appropriate for me to be using fragments of ancient greek melody, since I had been curious about Ancient Greek Music theory for some years, and had developed a fascination with musical traditions that had disappeared long ago. The idea that many of these ancient systems approached music in a way that would be considered quite foreign to us now had great appeal to me. I selected melodies that presented unusual melodic contours, which I transposed according to a transpositional matrix with the expectation of finding some unusual and interesting harmonic possibilities.

Through my reading of Peter Maxwell Davies in previous years, I decided to use, as he had done, a renaissance astrological “magic square” for the pre-compositional working. Davies used these mathematical formations to re-order series of pitch-class sets according to the special numerical order of the “magic square.”

It was in so doing this that several major structural elements emerged. These became some of the main features of the work that was to develop. As a result of re-ordering the pitches, one of the squares resulted in an entire row of the pitch D. It was this particular pitch that developed a special structural role within the work. After following up on a few other leads, it also became clear to me thatNichomachus, in his Excerpta 3 (2nd Century AD), had attributed the string of the Lyre named the lichanos meson to the planet Mars. It is this particular string which was recognised as the pitch D. And so I decided to set these relationships in stone from here. The piece would be concerned with the planet Mars, and the pitch D. There were also a series of tetrachords, relating to the fundamental tuning of the fixed pitches of the Lyre, that also developed a significance within the piece.

At this time I had been inspired by a name of a geological formation on Mars by the name of Ascraeus Mons. For me it gave an immediate and positive impression of a stark, barren, and austere formation. Though it also stimulated in me a deep sense of grandeur, and of course, the alien.

I had also been inpired by another formation within the same region called the Noctis Labyrinthus. These formations, for me, seemed to be highly evocative in many ways. Certainly of the landscape, that may not inhabit life as we know it, but appear to be full of life in terms of their landscape and geological formations.

Though, while making note of this inherent beauty, both structures have been prone to structural collapse and deterioration. It is this structural paradigm that seemed to stick with me during the composition of the piece. This became a significant element of the final section concerned with the Volcano: Ascraeus Mons.

The Setting of Boundaries

After a preliminary graphic sketch (a visionary attempt at conceiving a possible score) of the textural and temporal progression, it was necessary to devise a more specific macrostructure for the work. With a total duration of twelve minutes in mind, I used specific temporal divisions to devise a working macrostructure. It was also necessary to differentiate sections by way of their micro-material and sectional purpose. However, I wasn’t to know that my concept of the macrostructure was to continually change throughout the course of the creative process. And for this reason, the formal structure also gradually gave way to some other elements that were not motivated by the macro-structure itself.

I took four main structural concepts: the multi-layered, the labyrinth, atmosphere, and collapse as a basis for establishing structures. The multi-layered is reflected in the layering of musical idea. Each section of the chamber orchestra has, at many times, characteristic material only applicable to a given section (i.e.woodwinds). The labyrinth is developed through the complex pitch and tonal formations developed by the process of transposition and transformation with the re-ordering of pitch-class sets according to the Mars “magic square.” The atmosphere is maintained in the strings for the majority of the work. With incredibly long and sustained lines, the strings remain fairly stable (structurally) for the majority of the piece. The notion of collapse is presented in the work with the use of descending (and sometime ascending) glissandos which permeate the structure at both the micro-level and the macro-level. This notion of structural decay and collapse was also taken further with the gradual introduction of aleatoric writing toward the end of the piece. In some ways, this might indicate the breaking down of what might have been a constructivism formation.

Musically the work describes a programmatical journey (in the 19th century sense) from the Noctis Labyrinthus, and then westward toward the Ascraeus Mons over the Tharsis plain. Essentially the divisions listed below, are a series of ‘snapshot’s’ from which the musical material has been based. These images are described with brief description in the right column of this table.

At this time I had been inspired by a name of a geological formation on Mars by the name of Ascraeus Mons. For me it gave an immediate and positive impression of a stark, barren, and austere formation. Though it also stimulated in me a deep sense of grandeur, and of course, the alien.

I had also been inpired by another formation within the same region called the Noctis Labyrinthus. These formations, for me, seemed to be highly evocative in many ways. Certainly of the landscape, that may not inhabit life as we know it, but appear to be full of life in terms of their landscape and geological formations.

Though, while making note of this inherent beauty, both structures have been prone to structural collapse and deterioration. It is this structural paradigm that seemed to stick with me during the composition of the piece. This became a significant element of the final section concerned with the Volcano: Ascraeus Mons.

The Setting of Boundaries

After a preliminary graphic sketch (a visionary attempt at conceiving a possible score) of the textural and temporal progression, it was necessary to devise a more specific macrostructure for the work. With a total duration of twelve minutes in mind, I used specific temporal divisions to devise a working macrostructure. It was also necessary to differentiate sections by way of their micro-material and sectional purpose. However, I wasn’t to know that my concept of the macrostructure was to continually change throughout the course of the creative process. And for this reason, the formal structure also gradually gave way to some other elements that were not motivated by the macro-structure itself.

I took four main structural concepts: the multi-layered, the labyrinth, atmosphere, and collapse as a basis for establishing structures. The multi-layered is reflected in the layering of musical idea. Each section of the chamber orchestra has, at many times, characteristic material only applicable to a given section (i.e.woodwinds). The labyrinth is developed through the complex pitch and tonal formations developed by the process of transposition and transformation with the re-ordering of pitch-class sets according to the Mars “magic square.” The atmosphere is maintained in the strings for the majority of the work. With incredibly long and sustained lines, the strings remain fairly stable (structurally) for the majority of the piece. The notion of collapse is presented in the work with the use of descending (and sometime ascending) glissandos which permeate the structure at both the micro-level and the macro-level. This notion of structural decay and collapse was also taken further with the gradual introduction of aleatoric writing toward the end of the piece. In some ways, this might indicate the breaking down of what might have been a constructivism formation.

Musically the work describes a programmatical journey (in the 19th century sense) from the Noctis Labyrinthus, and then westward toward the Ascraeus Mons over the Tharsis plain. Essentially the divisions listed below, are a series of ‘snapshot’s’ from which the musical material has been based. These images are described with brief description in the right column of this table.

On the whole the micro-structure was freely composed using certain differentiations between sections to indicate how textures were to develop, evolve, and coalesce. This structure (indicated in the second column in the table above) follows a musical scheme defined by three different criteria. Type A represents physical space (i.e. solid, liquid, air), and gradually undergoes a metamorphosis from a reasonably stable texture to one that is more complex. Type B represents transitions in physical state (i.e. condensation, evaporation), and is characterized by more detailed textures. Type C represents material that is to be associated with the eruption of the volcano (i.e. re-occurrences of the ancient greek melodies) and the complex combinations and changes of physical state that may be present at any one time during a high-energy event.

The Composition of the Piece

The composition of the piece progressed over the period of five weeks. From the 15th – 28th July and from the 5th – 25th August.

By the time it became necessary for me to evaluate the title, most of the work had been completed, and so it was quite clear to me how the rest of the work would follow. Collaboration with Kathryn Barras allowed me to be able to work out a subtitle for the work that reflected the programmatical journey of the piece. The use of latin was, for the most part, for reasons of consistency, but also to emphasise, yet again, a sense of the alien, or the unknown.

It seems that, for the concert-going audience, there is pressure for the composer to use titles that allow the listener to relate to the work at a more personal level. However, I consciously was after a title that immediately reflected the impersonal. This was through a conscious desire and inner need for not wishing the audience to be able to relate to the piece on a personal level. I wanted the feeling to be one of mystery. The feeling of the unknown. Like the experience of the labyrinth.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

-----------------, ‘Labyrinth’, The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Ed., Vol. VIII (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), p564.

Boal, Augusta, The Rainbow of Desire: The Boal Method of Theatre & Therapy, trans. Adrian Jackson (London: Routledge, 1995), p16.

Butler, Christopher, Early Modernism: Literature, Music, and Painting in Europe, 1900-1916 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), pp25-6.

Ford, Andrew, ‘The Reticence of intuition: Sir Harrison Birtwistle’, Composer to Composer: conversations about contemporary music (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1997), pp54-5, 58-9.

Nietzsce, Friedrich, Twilight of the Idols and the Anti-Christ, trans. R.J. Hollingdale (London: Penguin Books, 1990), pp81-2, 91.

Smalley, Roger, ‘Some Recent Works of Peter Maxwell Davies’, Tempo, Vol. 84/1 (1968), p2.

[1] Smalley, Roger, ‘Some Recent Works of Peter Maxwell Davies’, Tempo, Vol. 84/1 (1968), p2.

[2] Butler, Christopher, Early Modernism: Literature, Music, and Painting in Europe, 1900-1916 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), pp25-6.

[3] Ford, Andrew, ‘The Reticence of intuition: Sir Harrison Birtwistle’, Composer to Composer: conversations about contemporary music (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1997), p55.

[4] Ford, Andrew, ‘The Reticence of intuition: Sir Harrison Birtwistle’, Composer to Composer: conversations about contemporary music (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1997), pp58-9.

[5] Nietzsce, Friedrich, Twilight of the Idols and the Anti-Christ, trans. R.J. Hollingdale (London: Penguin Books, 1990), p91.

[6] Nietzsce, Friedrich, Twilight of the Idols and the Anti-Christ, trans. R.J. Hollingdale (London: Penguin Books, 1990), pp81-2.

[7] Ford, Andrew, ‘The Reticence of intuition: Sir Harrison Birtwistle’, Composer to Composer: conversations about contemporary music (Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1997), pp54-5.

[8] Boal, Augusta, The Rainbow of Desire: The Boal Method of Theatre & Therapy, trans. Adrian Jackson (London: Routledge, 1995), p16.

The Composition of the Piece

The composition of the piece progressed over the period of five weeks. From the 15th – 28th July and from the 5th – 25th August.

By the time it became necessary for me to evaluate the title, most of the work had been completed, and so it was quite clear to me how the rest of the work would follow. Collaboration with Kathryn Barras allowed me to be able to work out a subtitle for the work that reflected the programmatical journey of the piece. The use of latin was, for the most part, for reasons of consistency, but also to emphasise, yet again, a sense of the alien, or the unknown.

It seems that, for the concert-going audience, there is pressure for the composer to use titles that allow the listener to relate to the work at a more personal level. However, I consciously was after a title that immediately reflected the impersonal. This was through a conscious desire and inner need for not wishing the audience to be able to relate to the piece on a personal level. I wanted the feeling to be one of mystery. The feeling of the unknown. Like the experience of the labyrinth.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY